Anatomy of a Book: Intro, Signatures & Text Blocks

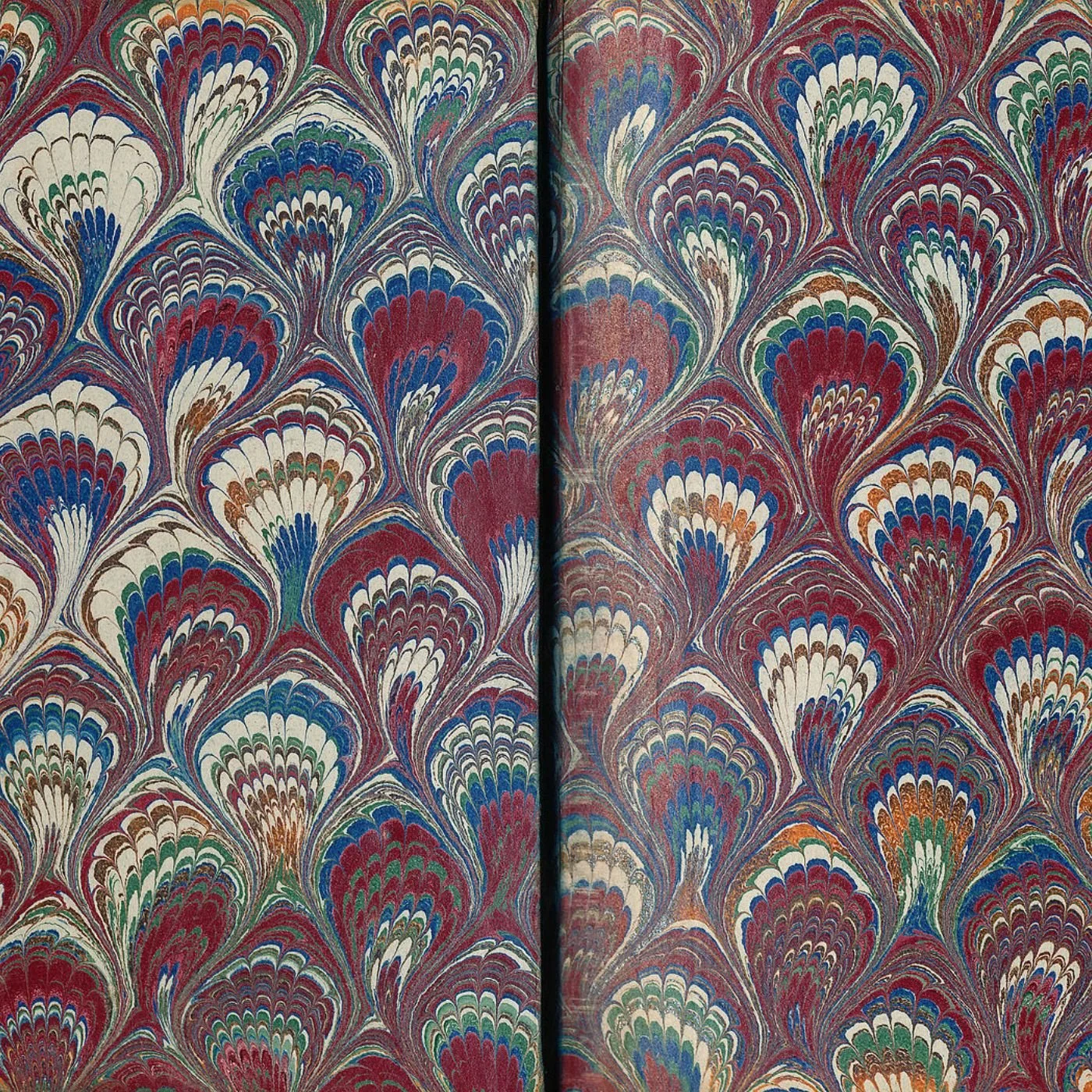

Marbled endpaper from a book created in Vienna ca. 1875

We are delighted to welcome our readers to a new series within our blog. This series, which we call Anatomy of a Book, details the core elements and components of a book. We will touch on the why’s & wherefore’s shortly. First, we ought to mention that this series will feature monthly over the entire year. Posts will be published on the 28th of each month and will each detail a different facet of bookbinding and book design.

Our aim is to accomplish these posts in a logical fashion, beginning from the heart of a book. As such, our first post deals with the signatures, text blocks, and initial bindings considerations of a book. More will be said of this process shortly.

First, it is important to note our rationale for carrying out this task. In our realm, the realm of occult literature and publishing, a vast number of book designs, layouts, and bindings present themselves. Numerous terms like “GSM,” “quarter-bound,” and “vellum,” are often encountered, to name a few.

These terms and designs, if misunderstood, may stifle or baffle the reader. At first glance, some of these terms may even appear superfluous or backgrounded in importance. Yet, each represents a set of components vital to the character and makeup of a book.

As such, our primary goal is to expand and enhance not only the appreciation of variety and form found within occult publishing, but also to aid the reader in selecting the book that will best fit their needs, desires, and preferences.

Secondary is the goal of enhancing the general appreciation of the craft that goes into any book, occult or otherwise. The traditions and methods of bookmaking are diverse and rich, and a basic understanding of book anatomy can greatly enhance the insight one gleans into the craft.

A ‘Four of Books.’ From Charta Lusoria. Charta was published in 1588 by Jost Amman

With this said, it is time now to turn to square-one and explore the makeup of a book. Today, we will discuss the book block, or text block, being the entire stack of folded and arranged paper forming the pages of a book.

A traditional book contains an anatomy quite like a person or animal: it has flesh, muscle, connective tissue, skin, a heart, and so forth. This focus on anatomy allows us to approach a book as a body, one constituted by multiple interworking parts.

As objects made to encase pages of paper — and, in turn, essential content — the book’s pages therefore serve as its heart and circulatory system. Yet, this heart itself contains a few important components. It follows that our initial exploration will deal with the most singular expression thereof: a single sheet of paper.

Paper comes in many forms and guises: they vary in thickness, weight, woven quality, and so forth. We look forward to detailing this variety in a coming blog post. For the sake of today’s work, however, we will take a sheet of standard paper as our example.

Imagine, or even take up at home, a single full piece of paper. The typical sheet will contain two longer edges and two shorter edges.

Should we lay the paper in front of us with the longer edges at the top and bottom of the orientation, we will find that folding the sheet exactly in half lengthwise produces what is essentially a small pamphlet. This singular pamphlet contains a front cover, two inside pages, and a back cover. Here, we’ve constructed a kind of microcosm of a book.

This folded sheet has a special name: it is called a folio, and it derives from the Latin word folium, meaning ‘leaf.’ This folio serves as the basis and foundation for the next steps.

Once again, take up a piece of paper at home, or in the mind’s eye. Repeat the process described above by folding the next sheet in half lengthwise across the longer edge. A second folio has now been created.

These two folios of the same size can be nested into one another: the spine, or folded edge, first folio can be inserted into the fold of the second folio and jogged, or tapped together, so that the two now form a singular object. We now find that our initial pamphlet has grown in page number, and the resemblance to a book has likewise increased.

A single, small signature consisting of 3 folios.

This set of two or more nested folios is called a signature, and it is these signatures that are subsequently stacked and sewn to create the text block of a text.

Signatures may vary in number, both in sheets or folios used, and in their own number within the text block.

Signatures themselves are subsequently placed atop one another, soon to be bound together through interwoven sewing patterns. For our purpose, let us say that we hold a signature containing 7 folded sheets of paper, or folded folios. By virtue of the multiplicity of folding, this equates to 28 pages. In this example, we are seeking to create a book consisting of 140 pages. In turn, we will take four more signatures to create five in total.

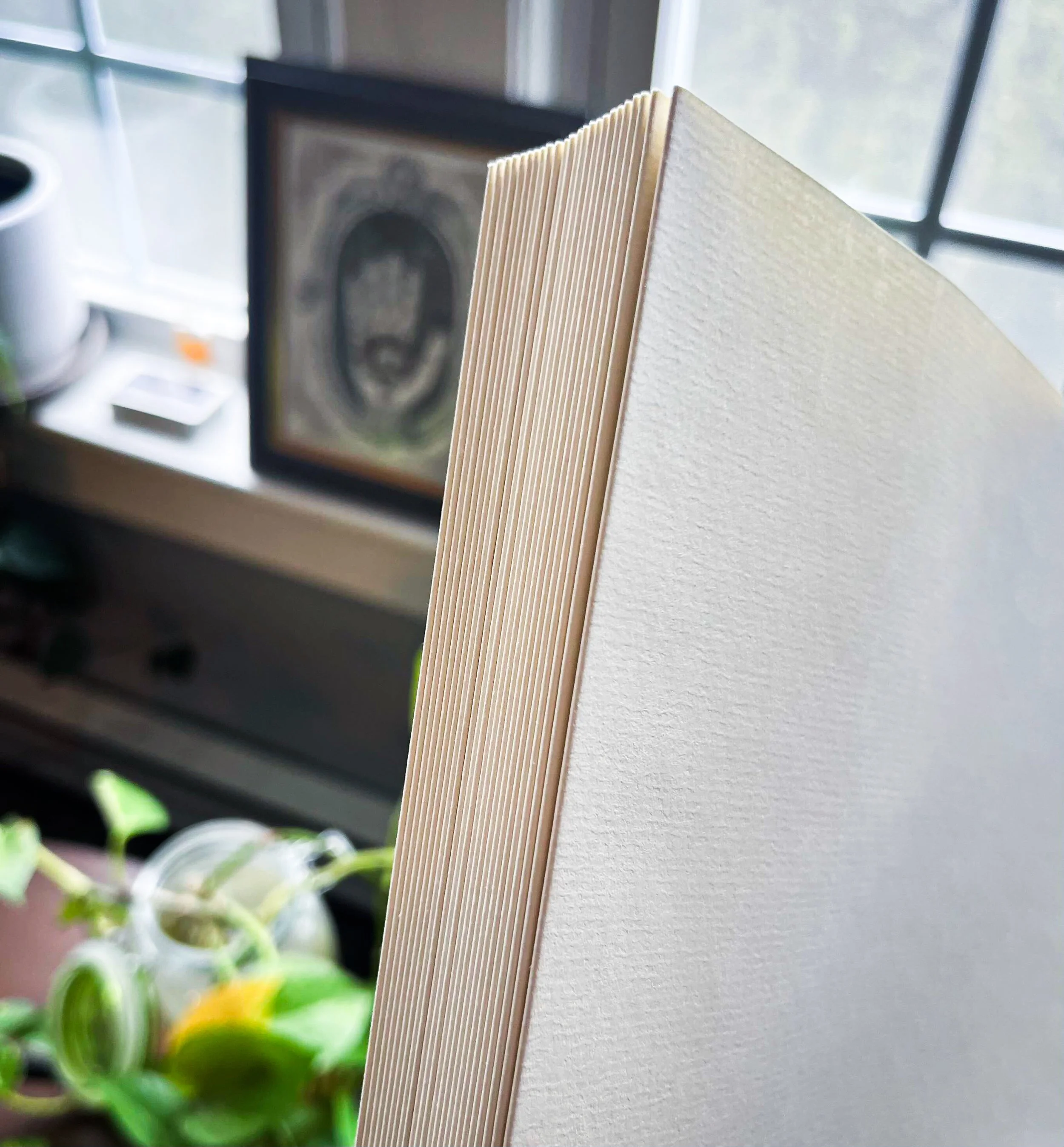

These signatures can be stacked together so that all their spines are in a row, just as we see in the image below.

A stack of signatures forming the unsewn, unbound book block. Oriented upright in this image.

At last, we have our unsewn and unbound text block: the collection of signatures that will now be bound together, forming the heart of our book.

What of this binding and sewing, though? There are many ways to accomplish this task, many of which we will detail in next month’s post. However, the principle is essentially the same in any case: sewing with various kinds of thread take place along the spines of these signatures, weaving them together along the text block.

This fastening process not only maintains the structure of the text block, but it holds the piece together in such a way that the entire form can ‘paged’ like a book while holding together firmly and uncompromisingly.

Indeed, this text block is the core of the book, and it will later be set and bound into a cover through various means. However, sewing is not the only option, as we will see with examples like perfect-bound books. Yet, for our example, this eminently common form of binding is going to be used.

Alternate book block angle, with signatures slightly fanned for view.

The integrity of the text block is vital to maintaining the structure and form of the book entire. Evened and leveled edges , optimal tightness and fastening, and quality of signature construction all funnel into the overall form and function of a book. These qualities serve an aesthetic purpose as well, and maintain degrees of form: some, a clean and pleasing look. Others, a ragged and untamed appearance. In these instances, form and function merge or lie in tension to create a unique object for storing written and artistic content.

It goes without saying that the function of the text block as a repository of such content also plays into its role as the heart of a book. While blank books or journals may serve as aesthetic objects in their own right — as many do in the world of book arts — some are of the conviction that books are content vehicles, most calling out to be filled.

And so, our journey into the creation of a book commences at the heart. The written and artistic forms that will full our book serve as the lifeblood of the work, circulating throughout a text and offering meaning and reflection to the reader.

Next week, we will detail the sewing and binding process: the process and structure that serves muscular system and connective tissue of a book.

A ‘Queen of Books.’ Again, from Jost Amman’s 1588 Charta Lusoria.

We look forward to sharing our this coming post with our readers, and we are eager to watch our writing grow into a book at the end of our series.

If nothing else, we endeavor to offer a greater sense for what goes into these object. Many defy their seeming simplicity, while others speak directly to it.

Which leads us to an ending consideration: books — like people — also have personalities, soul, and individuality. Until the enxt post, we reccomended taking a book off your home shelf, examining its design, and discerning what its individual perosnality speaks to you.

Onward to sewing & binding next week!

As always, we are grateful for our readership, and we look forward to your feedback.

All the best,

— The Occult Library staff